WHEN the sun rises over Rutenge village in Kamachumu ward, Kagera, the first smoke curls from the kitchen of Paskazia Muk’omukama, a 67-year-old mother and grandmother. The smell of burning firewood, mixed with the aroma of matoke, fills the morning air. For her, this is more than a routine. It is a lifelong rhythm.

“I grew up seeing my mother cook with firewood,” she says, fanning the flames beneath three stones that support a blackened pot. “My husband used to fetch it from the hills and the forest. When he got old, our sons took over. We don’t know any other way.”

For Paskazia, firewood is not a burden. It is heritage – part of the Kagera way of life. “Food cooked on firewood tastes different,” she says with pride. “It connects us to our ancestors.”

But behind her calm words lies a story repeated in millions of Tanzanian homes – a story of smoke, sweat, and survival. Across the country, women like Paskazia still depend on firewood and charcoal as their only sources of cooking energy.

The burden they carry

In Geita, Maria Magesa (42) rises before dawn. She walks three kilometers to collect firewood before tending her maize field. “If I don’t go early, others take what’s left,” she says. “Sometimes, I come back with just a handful of them, not enough to cook one meal.”

In Dodoma, Zawadi Mwenda (35), a mother of four, buys small bundles of firewood at the market. “Even charcoal is becoming expensive,” she sighs. “We hear about gas and clean energy on the radio, but it’s for the rich.”

In Morogoro, Asha Rajabu (28), a housegirl, speaks between coughs. “I cook with charcoal every day. The smoke chokes me, and my eyes burn – but we still have to prepare food three times a day.”

In Lindi, Neema Mtitu (31) spends nearly half her day collecting firewood. “By the time I finish fetching water, washing clothes, and cooking, there is no time left to rest,” she says.

And in Rukwa, Regina Joseph (54) remembers when trees were plenty. “Now, the forest is gone. We walk farther each year. But what can we use instead?”

For these women, cooking is not a simple task – it’s a daily struggle that consumes their time, health, and sometimes their hope.

The hidden danger of the kitchen smoke

Inside many Tanzanian kitchens, the fire burns, but so do the lungs. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), exposure to smoke from traditional cooking fuels contributes to respiratory infections, eye problems, and thousands of premature deaths every year – especially among women and children.

In Singida, Juliana Komba (47) shares her experience. “Every morning I cough and my chest hurts,” she says. “Doctors told me to avoid the smoke, but what else can I use?”

In Mbeya, Theresia Kasanga (39) once tried switching to charcoal. “It was cleaner, but too expensive. I had to resume using firewood. Now I mix both, depending on what I can afford.”

Across the regions, women are caught between poverty and pollution, tradition and transition.

Tanzania’s turning point

As the world prepares for COP30 in Brazil, where global leaders will renew commitments to fight climate change, Tanzania stands at a critical crossroads. The government has pledged to promote clean cooking energy – encouraging the people to use LPG, biogas, solar or electric stoves – as part of its national energy transition plan.

Statistics differ slightly. The World Wide Fund for Nature says that by 2020 63.5% of Tanzanian households used firewood as their main cooking fuel, while the other 26.2% used charcoal. In its 2022 reports, the Clean Cooking Alliance put the number of people using clean cooking fuels at 9.2%.

Data from “the impact of access to sustainable energy survey” conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics in 2021/22, show that 67% of Tanzania mainland households use firewood, while 25% use charcoal as their main source of cooking energy.

But the Strategy Document (2024-2024) says about 90 percent of Tanzanian households still depend on firewood and charcoal (63.5. Women, who carry the greatest burden, remain at the heart of this energy crisis – and must also be at the center of the solution.

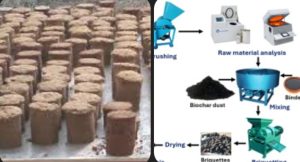

Across some towns, change is slowly flickering. In Arusha, women’s groups are experimenting with improved cookstoves that use less firewood. In Dar es Salaam, small startups are producing affordable briquettes made from agricultural waste. In Dodoma, young innovators are introducing solar-powered cooking systems in schools.

But for women like Paskazia in Rutenge, these developments still feel far away. “If clean energy reaches us, maybe our daughters and granddaughters will cook without smoke in their eyes,” she says softly.

A future worth hoping for

In Kwimba, Mwanza region, Rehema Juma (33) and her neighbors form small groups to fetch firewood together. They sing as they walk, turning hardship into solidarity. “Sometimes we laugh and say, one day we’ll cook by pressing a button,” she giggles. “Maybe it’s possible.”

In Tabora, Fatuma Salum (29) dreams of that day. “My baby sleeps on my back as I blow the fire,” she says. “If clean energy comes to villages like ours, it will save women’s lives.”

And in Tanga, Saumu Makame (37) sums it up simply: “Firewood binds us – our lives, our stories, our traditions. But it also burns our health and forests. I wish we could cook clean and still keep our traditions.”

From smoke to hope

Back in Kagera, as dusk falls, Paskazia’s kitchen glows with the soft light of embers. She wipes her hands on her khanga and smiles faintly. “I have seen many changes in my life,” she says. “Maybe this will be the next one – cooking without smoke.”

Her hope carries the weight of millions of Tanzanian women who dream of a cleaner, safer, and fairer future – one where no child coughs beside a smoky fire, and no mother spends half her life searching for fuel.

As Tanzania joins other nations at COP30, these women’s voices-rooted in villages, kitchens, and quiet endurance – must be heard. Their stories remind the world that the journey to clean energy is not just about technology or policy. It is about people – about women like Paskazia, Maria, Asha, and countless others – whose daily courage keeps Tanzania fed, even as they breathe in the cost of survival.