(Translated from Kiswahili by SK Media)

These animated cartoons have caused a crisis at Mwananchi Communications Limited (MCL) in Tanzania.

The government has seen the cartoons and claims they violate Rule 16 of the Online Content Regulations. As a result, it has suspended all the Online Media Services Licences of MCL for 30 days.

The government has however, not revealed contents of these cartoons to the public; but on October 2, 2024, in its statement, the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA) said MCL had published prohibited content that “threatens and is likely to affect and harm national unity and social peace of the United Republic…”

Clips of the alleged animated cartoons published by MCL were shared on some social media platforms in the country. Five days ago, they were shown in a special interview segment on Deutsche Welle (Voice of Germany), featuring men and women crying for their missing children, relatives, and friends, demanding explanations – even if “our loved ones were killed.”

This issue of people disappearing or getting arrested, abducted and others killed, was the main theme of the National Symposium organized by the Tanganyika Law Society (TLS) in Dar es Salaam last week, under the slogan: “Where Are They?”

Now, fear has spread among media owners: Whose licences will be suspended tomorrow, the day after, next week, or next month? Maybe it’s you, the publisher of an online media outlet. Maybe the owner of a radio or television station.

I worked at MCL for five years, serving as Public Editor – a link position between the public and the company that produces The Citizen, Mwananchi, and Mwanaspoti.

I found that when editors noticed an error, or something unfamiliar and unintended in their products, they were quick to report and even apologise to consumers of their products. This happened twice when I was with them.

Last week, according to the editors, they received feedback that their animated cartoons were giving an unintended message. They quickly removed the cartoons and apologised. But the government was on. Punishment.

If they decide to go to court, they might be delayed in getting what they are fighting for. Thirty days could turn into 60 or 90 or more. If they remain silent, that means where the case outcome could have corrected the law by clearing ambiguity, things would remain the same. They are counting the days. Today is day 10.

We can say that both TCRA and MCL forgot another – more important and honourable – path: The Media Council of Tanzania (MCT), where a decision could be made swiftly.

When we were preparing and later forming MCT, we envisioned and established a “Court of Honour.” The first to lead this court was retired Justice Joseph Sinde Warioba; he remains a key figure of the institution – wherever he may be – and for all subsequent judges.

This is an independent body within MCT, and it operates autonomously. Its decisions are accepted and respected. It is easy to access and has almost zero costs. In this case, neither party went there.

Yet, there is evidence of citizens from various social ranks in the country, including the Vice President and other government leaders, who have tasted the competence and swift delivery at MCT, and continue to respect its decisions.

Now, let’s return to our animated and still cartoons. Does the government have the ability – professionally, legally, or constitutionally – to examine, judge, and direct which cartoons are appropriate and which are not? Isn’t this akin to deciding which news or information should be broadcast and which should be withheld?

If so, wouldn’t that mean the government has hijacked the media; or blocked the intellectual channels of journalists, editors, and media owners? In short, wouldn’t the government have interfered with the intellectual freedom of professionals and even citizens – by instilling fear?

Here, even media owners who haven’t been affected will start to think and instruct their outlets to publish only “what pleases Caesar.”

Regarding these animated or still cartoons, the government is strongly advised to put its hands off. Why?

Cartoons are the opinion of the cartoonist or creator – the chef. They are the result of what the artist has seen, heard; what is happening, analysed, predicted, thought, or what is being whispered in secrecy. Even dreams.

Cartoons are “food” for the reader. Every reader draws meaning from them based on their level of knowledge, breadth of thought, and depth of understanding.

Cartoons are a realm in journalism where, after presenting all the facts, you leave the reader free to interpret the message as they see fit – based on their environment, how they relate, live, and hear, and how they connect it with their experience.

Here, you cannot impose an interpretation on anyone. Even the cartoonist may tell you that yesterday they meant one thing, but today they see their drawing having a different meaning. What happens after the drawing can influence your understanding of the cartoon and even alter your earlier meaning.

For this reason, the government has no place in deciding that a particular cartoon has a negative meaning. This could only occur if someone comes forward and files a complaint, saying the cartoon “affected them negatively,” and the complainant is identified by name, gender, ancestry, age, residence, and personal preferences.

As we discussed above, cartoons almost complement what you already have at heart or in real life experience. Some may be incomprehensible, as the individual lacks the knowledge, understanding, or experience to grasp them. Some may evoke joy within you. Some may warn or depress. Others may tickle and surprise you.

This is where we urge the government not to rush to impose punishment of whatever form and colour. If you rush to punish the cartoonist, you may also want to punish those who enjoyed and appreciated the cartoons. What a dilemma!

You will kill freedom of expression, rob people of knowledge and information, and infringe on everyone’s freedom to think.

It is crucial to remember the consequences of shutting down a media outlet. In my book, Uhuru Gerezani (Freedom imprisoned) (2008), I listed 28 negative effects resulting from suspending, halting, or shutting down a media outlet. The book was published by Hali Halisi Publishers Limited, the publishers of the MwanaHalisi newspaper.

Everyone still has the opportunity to benefit from this book. I recently visited the MwanaHalisi offices and picked up a copy. They still have them. Let’s review together. Let’s think together without uprooting the foundations of freedom, rights, and knowledge.

Let us agree: The project of “editing” people’s thoughts in their minds is not only impossible, but it is also unproductive, and it may undermine the government in the eyes of the people who gave it authority – its citizens.

Therefore, it is essential to amend, correct, or entirely abolish laws that keep freedom of the press, the right to access of information and news; and the freedom of media outlets, in the hangman`s noose.

__________________

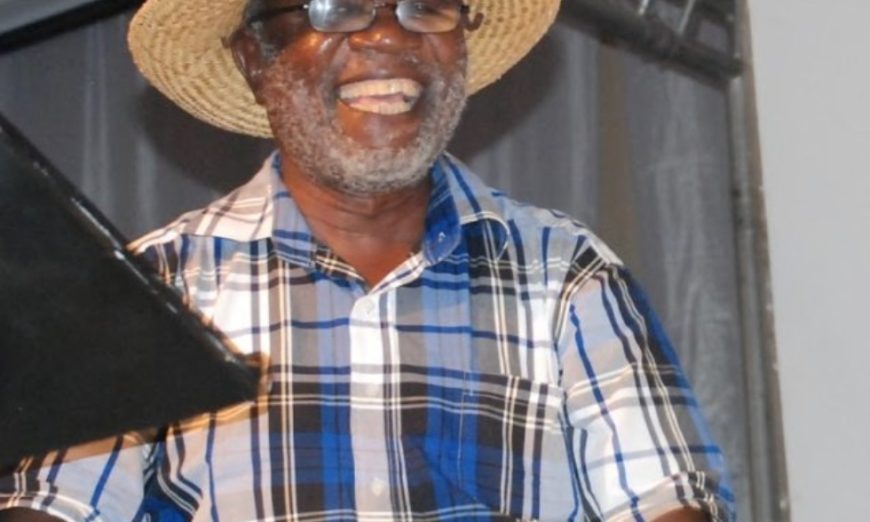

*Ndimara Tegambwage is author of over 20 titles; media trainer and mentor. He is former editorial advisor to MwanaHalisi. He can be reached at: +225 713614872 and +255 763670229.