Translated from Kiswahili by Sauti Kubwa. This article was first published in MwanaHalisi weekly on 24th October 2024)

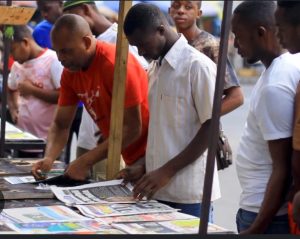

IF there are people living in great fear in Tanzania right now, journalists are among them.

I’m referring to investigative journalists. The pursuers. Those who seek to sniff out, see, hear, dig, discover, verify, analyze, and prepare the “meal” for the reader, viewer, and listener. These journalists are now gripped by fear.

This fear stems from the environment created by those referred to as watu wasiojulikana – the “unknown people.” (These are marauding gangs that have systematically caused disappearance of people through trickery and abduction. Some abductees have often been found in near-death condition, having been tortured; and others found dead and their bodies abandoned in bushes; or wrapped in cellophane bags and tossed in rivers).

Remember, this is happening in a country long known as a “fortress of peace.”

Two weeks ago, the Tanganyika Law Society (TLS) released, at their symposium in Dar es Salaam, a list of over 70 people who had been reported missing, arrested, tortured, and killed. Some of the survivors were able to recount their ordeals.

We now find ourselves in an atmosphere of endless tears from those who have lost relatives and friends; amidst sobs of mourners; and among those who have lost hope of ever seeing their loved ones, who were abducted and never returned.

In this environment, we have seen no investigative reports on the “unknown” and the “unseen.” It is safe to say, journalists have not failed or refused to act. No. Rather, they too have been paralyzed by fear, like the rest of society, or are simply “moving very slowly.”

It is also important to note that we are living in a time of extreme authoritarianism, especially since 2019, during the preparations for the “great vote theft” in the local government elections, followed by the unprecedented theft during the 2020 General Election, which has been dubbed, Uchafuzi Mkuu – Unprecedented Electoral Pollution.”

Blatant acts of vote theft – committed by the authorities in broad daylight – along with threats issued against anyone daring to oppose the government, created an atmosphere of chaos, with a war-like tension.

A thief begins by calculating, “If I’m not caught, it will be fine.” Nape Nnauye, the former Minister of Information, said that after you finish stealing, you pray to God for forgiveness.

The thief also considers the alternative: if caught, what will he do? He may fight back with all his might, even to the point of killing. This, again, creates a war-like situation.

But there’s a third element: what will those who catch the thief do? They may bring him to justice, or in a fit of anger, take his life. This, too, fosters an election environment resembling warfare.

It is in this context that we find the journalist. What was once considered a peaceful arena is being turned by the authorities into a space where jungle tactics prevail, and the journalist becomes a hostage.

In the election arena, this situation has persisted to the present day. It’s a field of chaos, a battlefield where Tanzanian journalists are not accustomed to working. It’s a tough and dangerous environment that a journalist cannot endure without building their strength, “upgrading” themselves, and, if possible, receiving support.

Working in such an environment requires cooperation, professional camaraderie, and solidarity among peers. It demands collaboration among journalists, media owners, and unity within and across the entire journalism profession. It’s an environment that compels all involved to operate as a family.

Therefore, I argue that this sense of family is not just important; it is essential for media stakeholders, especially at a time when the safety of citizens, including journalists, is threatened by both the unknown and the known.

In this environment therefore, it’s crucial to know each other, to recognize one another: who is doing what, where they are, and how they are faring (personally and within their company or organization) in five key areas:

First, does the person have freedom and security? Are they being oppressed? If so, how, and why? What can we do together to relieve this oppression?

Second, do they have professional capacity? If they lack the necessary skills, or their capacity is limited, we must identify this and collectively find ways to guide them to where they can acquire the required skills, or we must help them gain these skills ourselves.

It’s important to understand that lack of professional capability can lead to deficiencies or mistakes, which may result in ethical breaches, potentially leading to trouble for the individual.

Third, do they collaborate with other stakeholders in the profession? Collaboration builds solidarity. Journalists at all levels who know each other and work together remain united in fighting for press freedom, their rights and welfare, and the integrity of their profession and the industry.

Fourth, journalists come from various companies, organizations, institutions, and even the government. There’s a need to build relationships across all the areas where journalists work.

The solidarity between journalists and the companies, organizations, and institutions they represent strengthens the case for advocating for the rights and freedoms of media that investigate, collect, process, analyze, and disseminate information, as well as follow up on outcomes.

Fifth, solidarity with the community and civil society organizations. In short, the media and civil society need each other. A society that fights for or builds democracy—through the rule of law—needs reliable and diligent media and journalists to provide accurate and truthful information about what’s happening, so that it can make informed decisions.

On the other hand, the media needs the community as its source of information; not just stories that bring happiness to society, but also those that highlight the great work and talents of journalists.

The key point is that strong civil society organizations are one of the main pillars of the media, particularly in standing by them and fighting for their welfare, rights, and freedom of expression.

Whatever the case, in the current environment of palpable fear among journalists, we need wisdom to move forward from where we are.

I propose that every responsible media organization should do the following three things:

First, investigate and document the source of the fear affecting citizens and journalists in the current environment.

Second, use the findings from this investigation to immediately begin educating journalists on how to work in tough and dangerous environments.

Third, immediately start building relationships between journalists and media organizations to foster the solidarity needed to fight for media rights and freedom.

********************************************************

Ndimara Tegambwage is the Chairperson of Media Freedom Tanzania (MFT). Phone: +255 763 670 229