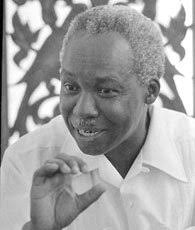

A decade ago, Dr. Azaveli Lwaitama, one of Tanzania’s towering public intellectuals, pronounced, “the Tanzania project is in tatters.” Dr. Lwaitama was reflecting on Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere’s major governance achievement in nation building.

Tanzania has never been a more distant idea than it is now since the beginning of the last decade. Politics of hate have eaten up the nation.

There may be some people who will be wondering why Dr. Lwaitama is talking about Tanzania in terms of projects and ideas. Is Tanzania not a concrete reality, an internationally recognized sovereign state?

To me, as a permanent student of Constitutional Political Economy, the question of legitimizing the state and its actions as the best means of maximum efficiency and utility, judging conditions or rules that are efficient, and discerning and studying the political systems to maximise efficiency where the outcome of collective choices are considered “fair,” “just,” or “efficient,” sits at the center of nation building.

In interrogating Dr. Lwaitama’s pronouncement in which its gravitas is nationalism, I will apply constitutional political economy to discuss the current state of affairs in matters nation building. So, here we go.

Although the notion of a nation as an idea is an old one, it is Benedict Anderson’s 1983 book, “Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism,” that offered the most cogent articulation of the concept and, in so doing, shaped the contemporary study of nationalism.

Anderson defined nations as a social construct, political communities that live in the imagination of the people who ascribe to them. A concrete community is one whose members interact in one way or the other on a sustained basis.

Nations are not concrete because “members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their-fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”

In essence, then, belonging to a nation is simply the sense of connectedness with people one does not know and is unlikely ever to meet. The intellectual problem of the study of nationalism is understanding why and how people develop or fail to develop this belonging. Of note is the fact that this connectedness is not necessarily unproblematic.

Anderson puts it, “regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep horizontal comradeship. Ultimately it is this fraternity that makes it impossible, over the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings.”

The meaning of Dr. Lwaitama’s pronouncement should now be clear. It is a failure of the imagination. The failure to develop and propagate a national narrative alluring enough to nurture a “deep”, horizontal comradeship” beyond politics.

The reason for the failure of Tanzanian nationalism in modern times is a subject of historians to ponder. When the history is written, four squandered opportunities will stand out.

The first was in 1992. The transition to multiparty politics afforded our leaders opportunity to set the country on a different political trajectory. Parochial politics got the better of them.

The second came in 2013. The process of having a new constitution was unleashed only to find out it was a project hatched by the egg of impunity.

The third one came in 2015 when Tanzanians were craving for a leadership that would restore national values. When President John Magufuli got into power, the country was full of hope. But the decision by Magufuli’s administration that “wealth” was more important than people disappointed well wishers of this nation.

Magufuli himself metamorphosed from an erudite fiery nationalist to a parochial acquisitive politician.

The Samia’s administration was cheered in the expectations of inclusive politics. It is now clear that, she is tearing up the political covenant, and she is going back to the fifth phase government’s doctrine of wealth above all else.

But Thomas Hobbes was right when he wrote; “Covenants without the sword, are but words and of no strength to secure a man at all”. The question is; how do we make our sword? The answer lies in learning from history.

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

Are we doomed to become our past, to repeat the mistakes and history? In this 2021 of President Samia, the parallels with the past are disturbing.

The government appropriates the liberation fight and wastes little time undoing all its achievements; a new administration threatened by the very arguments that falled the the 5th phase government and, within a few months put us back on the path of dictatorship and penury.

A President who seems more interested in consolidating her own power than delivering on her political party’s campaign promises, who leads a superficial and fraying political inclusiveness which papers over and heightens rather than resolve social and political divisions.

When people find they are in a sick relationship, they start talking if they want to restore harmony. Tanzania is for the most part an abusive relationship. It is about time we start talking about this.

This is ought to be difficult conversation but very important so that we can have a new governance dispensation. A dispensation that will give us a sword for our covenants.

As we celebrate 60 years of independence, this is a conversation we must embrace however uncomfortable it may be.

“If a factory is torn down but the rationality that produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory.

If a revolution destroys a government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves”, wrote US philosopher Robert Pirsing, in his Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

In Tanzania, we have tried everything except reform the “systemic patterns of thought” that generated a repressive and kleptocratic regimes of the last six decades, patterns of thought that find their genesis in the attitudes and divisions of almost eight decades of the colonial rule that preceded them.

Now this is not what it might sound like; blaming the past or the colonialists for our current predicament. It is actually and indictment of the independence generation which failed to substantially dismantle or reform the system of elitism predicated on political, social and economic favouritism, the extraction and theft of resources from the poor and the concentration of power in the hands of a privileged few. It is an indictment of the current generation that is following in their footsteps, entrenching rather than over throwing the system.

The late Donella Meadows, in Thinking in Systems- A Premier described a system as a “set of things- people, cells, molecules, or whatever-interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time,” and invited us to consider the implication of the idea that any system, to a large extent, causes its own behavior.

It is the nature of “Tanzanian democracy”, the relationshipship between its various components-voters, rulers, police, soldiers, judges, journalists, media owners, businessmen, legislators, etc-; are what produce and reinforce the patterns of repression and inequality, of tribalism and corruption, ineptude and poverty and marginalisation, that we are so familiar with.

It is no about bad leaders versus good leaders. This we should have seen when the new administration replaced the kleptocratic Magufuli’s administration, only to end up with the same result.

It is not about the stupidity of voters because, whether we vote in wise or corrupt leaders, the system will encourage them to be vain and corrupt, and will either reward them with riches when they do or condemn them to poverty, exile or worse when they don’t.

As we think and rethink of our journey for the past sixty years, our nation building project should be paramount. In this discourse, a new system of governance is imperative. It is no secret that the forces against this imperative are immensely grounded with threats and propaganda but we must no let them take us for pumpkins any more.

If we collectively decide to allow a Tanzanian project remain in tatters after sixty years of independence, we will be doomed to face the consequences that Maya Angelou wrote about in; “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings”.

The caged birds have been singing for sixty years. Singing they must stop.