RWANDA’S decision to suspend its 2024-2029 bilateral aid program with Belgium marks a significant moment in the two nations’ diplomatic and development relationship. This move, announced by Rwanda’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs on February 18, 2025, signals growing tensions, particularly over Belgium’s alleged role in undermining Rwanda’s access to international development financing.

It emanates from Belgium’s active campaign for international financial sanctions against Rwanda, which is accused by some Western and African powers for allegedly being involved in the Eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where M23 rebels have been fighting the DRC forces for years. Rwanda’s statement emphasises:

“As the international community is being called upon to support the mediation process mandated by the African Union and the joint EAC-SADC summit to resolve the crisis in Eastern DRC, Belgium has led an aggressive campaign, together with DRC, aiming to sabotage Rwanda’s access to development finance, including in multilateral institutions.

“…Rwanda will not be bullied or blackmailed into compromising national security. Our only aim is a secure border and an irreversible end to the politics of violent ethnic extremism in our region. Rwanda needs peace and a durable solution, and no one should continue to tolerate the cycles if conflict which continually recur because of the failure of the DRC government and the international community, decade after decade, to fulfil their commitment to dismantle the UN-sanctioned genocidal FDLR militia, and protect minority rights.”

Rwanda accuses Belgium of politicising development. This decision, which follows a long history of cooperation between Rwanda and Belgium, dating back to the colonial period and post-independence development agreements, quickly drew the attention of Dr. Azaveli Lwaitama, a retired senior lecturer in Linguistics and Philosophy of the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

Speaking to SAUTI KUBWA on the matter, Dr. Lwaitama commends Rwanda for the “boldness and clarity on the issue of what the international community ought to do to help African peoples and governments solve African problems peacefully relying on African institutions and in a manner that respects African Ubuntu sensibilities.”

He says: “Belgium should be the last country in Europe to want to use so-called aid, which ought to be compulsory and not conditional reparations for King Leopold’s gross historical misdeeds in the Congo, which misdeeds contributed to the creation of the Banyamulenge problem in Eastern DRC, to promote a solution of the Eastern DRC conflicts that permit the FDLR militia that committed genocide in Rwanda in 1994 to remain in DRC carrying out genocide against the Banyamulenge in DRC as well as a plan return to Rwanda to finish the genocide business they were stopped from completing (in 1994) by Paul Kagame and his RPF colleagues.

“Belgium ought to be condemned by all progressive forces, and Rwanda ought to be commended for exercising its sovereignty and its Pan African spirit of never again to allow King Leopold’s gross historical misdeeds to be repeated on the African soil.”

Historical Context: Rwanda-Belgium Relations

Belgium, as the former colonial ruler of Rwanda, has had extensive post-colonial ties with the East African nation. Since Rwanda’s independence in 1962, Belgium has played a key role in the country’s development agenda, providing financial aid, technical expertise, and investment.

The two countries have engaged in multiple bilateral treaties, focusing on governance, education, health, and infrastructure development. Over the decades, Belgium has been a primary development partner for Rwanda, with agreements such as the 2019-2024 bilateral aid framework, which committed millions of euros to Rwanda’s development projects.

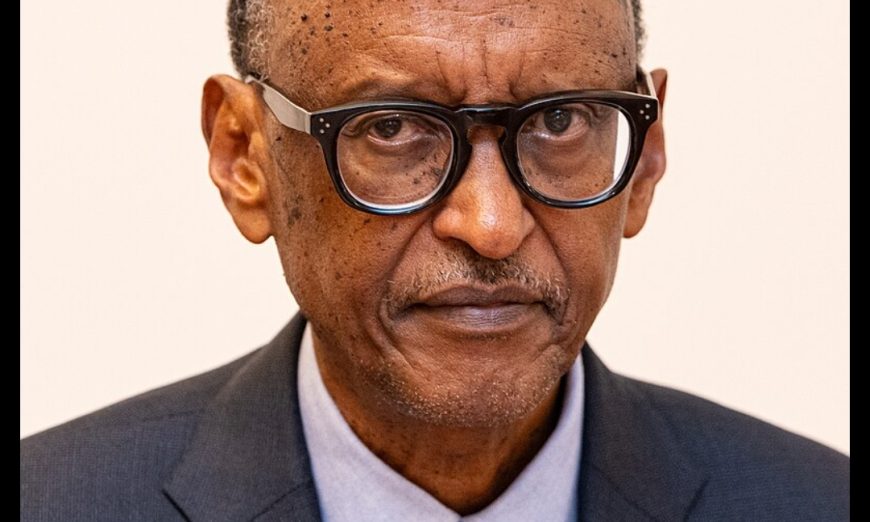

However, Rwanda’s leadership, under President Paul Kagame, has increasingly pursued economic independence and diversified partnerships, reducing reliance on traditional Western donors.

Precedents in Development Aid Suspensions

Rwanda’s move is not unprecedented. It adds to a number of similar cases that show how severing diplomatic ties have often been a tool for post-colonial nations to assert independence, protest foreign policies, or push back against perceived injustices.

Over the past six decades, developing nations have taken similar stances against developed nations, challenging the dynamics of foreign aid. One notable example is Egypt’s suspension of U.S. aid in 2013 following political tensions over the military’s ousting of President Mohamed Morsi. Similarly, in 1975, India rejected further development aid from the United Kingdom, stating that it wanted to shed its dependency on colonial-era assistance.

It may be similar to Julius Nyerere’s incident in 1965, when Tanzania’s first president, suspended diplomatic relations with Britain over its handling of Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI). Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), under the white-minority government of Ian Smith, unilaterally declared independence from Britain on November 11, 1965, without British approval and without granting majority rule to the African population.

The British government, led by Prime Minister Harold Wilson, opposed the declaration but failed to take strong enough action to dismantle the white minority regime. In response, Nyerere, a staunch advocate for African liberation, accused Britain of failing to act decisively against the illegal Rhodesian government. As a protest, he cut diplomatic ties with Britain, making Tanzania one of the first countries to take such a strong stance.

The suspension lasted until Britain took more concrete measures against Rhodesia. This move highlighted Nyerere’s commitment to African nationalism and decolonization, reinforcing Tanzania’s position as a leading voice in the fight against colonialism and white minority rule in Africa.

One may, as well, recall the 1958 Guinea-France tension, when Guinea, under President Ahmed Sékou Touré, voted “No” in a referendum on continued association with France, and the country declared full independence. In retaliation, France withdrew all financial and technical aid, but Guinea refused to back down. This effectively severed ties between the two nations for several years.

These cases illustrate how developing nations, particularly those with rising economic and political confidence, sometimes resist development aid when it is perceived as a tool for political leverage. Rwanda’s suspension of Belgian aid fits within this broader trend of asserting sovereignty in development partnerships.

Potential Impacts of Rwanda’s Decision

Rwanda’s suspension of Belgian aid could have several consequences:

Diplomatic Repercussions: The move may strain Rwanda-Belgium relations and affect diplomatic engagements in regional and global forums. Belgium, as an EU member, could influence broader European Union policies toward Rwanda.

Economic and Development Effects: Rwanda has made significant economic strides in recent years, but external funding remains crucial in key sectors. The loss of Belgian development assistance could slow projects in health, education, and infrastructure unless alternative funding sources are secured.

Regional and Global Significance: Rwanda’s decision sends a message to other African nations regarding their ability to challenge Western aid conditions. This could influence future diplomatic negotiations between African countries and Western donors.

Geopolitical Realignments: Rwanda may strengthen ties with other international partners, such as China, Russia, or Gulf nations, who offer development assistance with fewer political conditions.

Rwanda’s action against Belgium underscores a growing shift in development diplomacy, where a number of African nations are increasingly willing to push back against traditional Western donors. While this move asserts Rwanda’s sovereignty, it also carries risks, particularly if alternative funding sources fail to compensate for the suspended aid. The coming months will reveal how Rwanda navigates this new phase in its international relations and whether it will set a precedent for other nations in similar situations.