THE world prepares for COP30 in Belém, Brazil, opening on November 10, 2025. In a special way, Africa faces a defining test. With recurrent droughts, floods, and food insecurity threaten millions of livelihoods, the continent’s vulnerability to climate change is undeniable.

Yet amid these recurring crises, one truth continues to haunt Africa’s development story. Gender justice remains an unfinished business.

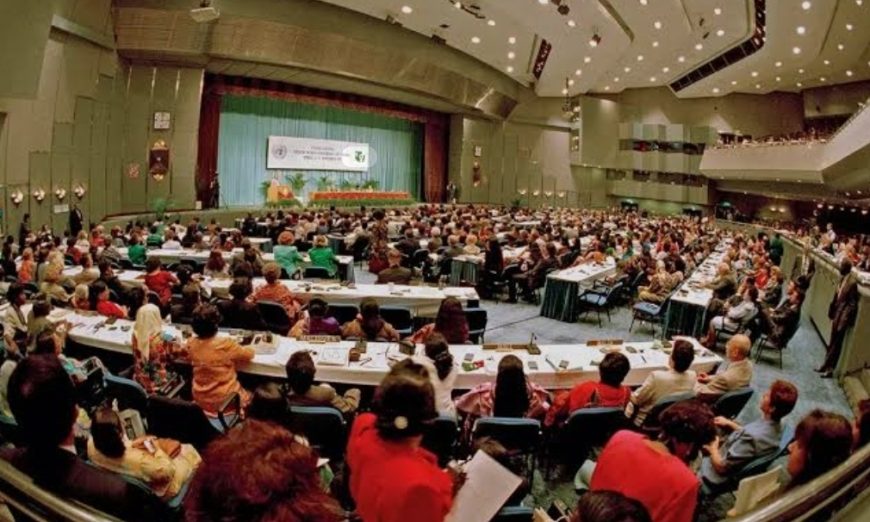

It has been forty years since the 1985 Nairobi World Conference on Women and thirty years since the landmark Beijing Platform for Action (1995), which promised to dismantle the structures of inequality that kept women at the margins.

According to UN Women, the Beijing Platform identified twelve critical areas for action, ranging from political participation to economic empowerment and environmental management.

Yet four decades later, Africa’s women are still fighting for inclusion, not recognition. They remain at the edges of power, under-resourced, and often excluded from the climate decisions that shape their survival. The climate crisis has exposed what Beijing missed: policy without power redistribution changes little.

As Tanzania leads Africa’s preparations for COP30, the continent has an opportunity, and a responsibility, to place gender justice at the heart of its climate agenda, ensuring that promises translate into concrete action.

Gender-responsive climate financing

Across Africa, climate funds often bypass women’s organizations and grassroots initiatives. According to a 2022 report by the African Development Bank, bureaucratic bottlenecks and male-dominated financial institutions limit women’s access to climate adaptation resources, reducing the effectiveness of projects aimed at the most vulnerable communities.

At COP30, Africa needs to push for gender-responsive climate financing, which includes direct funding for women-led climate initiatives; mandatory gender budgeting in all adaptation and mitigation projects; and transparent reporting that tracks fund allocation and outcomes for women.

Some experts argue that financial inclusion is the foundation of gender justice. Without it, participation risks remaining symbolic.

Equal representation in climate decision-making

Forty years after Beijing, African women remain underrepresented in key climate governance spaces. The Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) report shows that at COP27 in Egypt, fewer than 35 percent of African negotiators were women.

At the national level, women occupy only a fraction of senior roles in environment and finance ministries, meaning critical policy decisions continue to reflect male-dominated perspectives.

To correct this imbalance, African delegations at COP30 must adopt gender parity rules, ensuring that women negotiators, scientists, and civil society leaders actively shape Africa’s position. According to analysts, women bring crucial insights into issues like food security, water management, and climate-related health challenges. These perspectives are too often overlooked in male-dominated policy circles.

Secure land and resource rights for women

Land ownership is a critical determinant of climate resilience. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), women across most African countries still own less than 15 percent of agricultural land, a factor that severely limits their ability to implement climate-smart agriculture or participate in adaptation projects.

At COP30, African leaders must commit to reforms that secure women’s land and resource rights. This includes revising discriminatory inheritance laws and integrating women’s land tenure into national and regional climate resilience strategies.

Education, technology, and green skills for women and girls

The climate transition increasingly relies on technology, digital solutions, and scientific innovation. Yet studies show that women and girls in Africa remain underrepresented in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields and green economy initiatives.

According to a 2021 UN report on women and climate, this gender gap in knowledge and skills limits women’s ability to innovate and lead adaptation projects.

African governments must therefore prioritize education and capacity-building for women and girls, including scholarships and training programs in renewable energy, climate science, and data analytics; support for women-led green startups and enterprises; and integration of climate and gender modules into school curricula.

Accountability and gender-disaggregated data

Perhaps the greatest failure since Beijing has been the lack of accountability. According to a UNFCCC review, few African countries currently track gender-disaggregated data on climate fund allocations or participation in decision-making. Without such data, policies cannot be evaluated, and progress cannot be measured.

At COP30, African governments should commit to tracking the proportion of climate funds reaching women; measuring women’s participation in national and continental climate committees; and publishing annual progress reports aligned with the UNFCCC Gender Action Plan.

Apparently, independent monitoring by civil society and journalists is essential. Experts emphasize that what is not measured cannot be funded, and what is not reported will not change.

What 40 years after Beijing have missed

The Beijing Platform envisioned transformative change, yet much of Africa settled for symbolism. Gender desks exist in ministries, but often without budgets or decision-making authority. Policies proclaim equality, but political will lags. Women are visible, but not empowered.

Now, as climate shocks accelerate, these gaps are no longer abstract. They have real consequences. When women are excluded, adaptation fails. When they are denied land or finance, communities remain vulnerable. When they lack education and technology, innovation stalls.

COP30 is a moment for Africa to correct this trajectory. The continent has the chance to ensure that gender justice and climate justice are inseparable, turning decades of unfulfilled promises into actionable progress.

Africa’s leadership at COP30, spearheaded by Tanzania, can set a new global standard – one that fuses climate justice with gender justice. Governments, negotiators, and civil society must act decisively, ensuring that women’s voices are not just heard, but central to all climate strategies.

If Africa succeeds, it will not only amplify its moral authority on the global stage but also accelerate resilience, innovation, and inclusive growth at home. The question is no longer whether gender matters. It is whether Africa, forty years after Beijing, will finally act like it does.