EVERY general election season in Tanzania since 1995, has brought with it the question of constitutional reform and its urgency.

The first main opposition party after the return to multi-party politics in 1992 – NCCR-MAGEUZI; had the message in its full wings: National Convention for Constitutional Reform.

The demand and its urgency stem from the 1977 Constitution – a relic of one-party authoritarianism – ill-suited for a genuinely competitive multiparty democracy. But all subsequent governments have ignored citizens’ demands for a new order.

The opposition, frustrated by the lack of progress, often wonders:

“Should we even bother to contest under this flawed system? Shouldn’t we just suspend politics until a new constitution arrives?”

History across Africa offers a clear answer: No!

From Lusaka to Lilongwe, Accra to Dakar, and Nairobi, opposition parties have defeated entrenched ruling parties without waiting for a constitutional overhaul.

The lesson is that politics does not stop for constitutional reform. Instead, political change often comes first – paving the way for constitutional renewal later.

Zambia, Malawi, Ghana, Senegal, and Kenya present important lessons for Tanzania.

Zambia: Economic collapse opened the gates

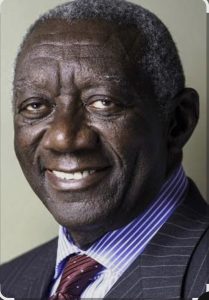

In 1991, President Kenneth Kaunda’s UNIP, which had ruled Zambia since independence, was voted out by Frederick Chiluba’s Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD). This happened under the old constitutional order, with only limited amendments to permit multiparty elections.

What drove change was not legal reform, but a collapsing economy, mounting public anger, and the unity of trade unions, urban activists, and the opposition.

The MMD spoke with one voice, presented a clear alternative, and capitalised on popular fatigue with Kaunda.

Lesson for Tanzania: Economic discontent and ruling party fatigue are potent forces. If the opposition can unite and offer credible alternatives, constitutional flaws will not prevent change.

Malawi: The fall of the “Life President”

Two years later, Malawi followed suit. President Hastings Kamuzu Banda, who had crowned himself “Life President,” was ousted through the ballot box in 1994.

Multiparty politics had been restored after a referendum, but the constitution was not fundamentally re-written.

Here, popular rejection of authoritarian abuses and regional grievances created a fertile ground for Bakili Muluzi’s United Democratic Front (UDF). Civic groups amplified the demand for change.

Lesson for Tanzania: Public mobilisation and coalition-building across regions matter more than waiting for perfect legal frameworks.

Ghana: Term limits as a game-changer

By 2000, Ghana demonstrated the power of credible institutions, even under an imperfect constitution. President Jerry Rawlings’ National Democratic Congress (NDC) had dominated politics since the 1980s, but the 1992 constitution introduced presidential term limits. When Rawlings stepped aside, his successor lost to John Kufuor’s New Patriotic Party (NPP).

The institutions did not magically become democratic overnight. But term limits, combined with an organised opposition and a credible program, created the space for transition.

Lesson for Tanzania: Even flawed constitutions can be leveraged if the opposition prepares programmatic alternatives and exploits institutional openings.

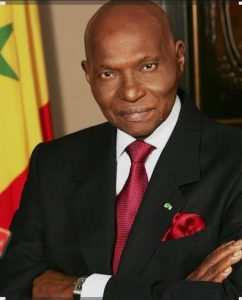

Senegal: Persistence and unity pay off

In 2000, Senegal’s Socialist Party, in power since independence, was finally defeated. Abdoulaye Wade, a perennial opposition figure, united diverse groups behind his candidacy. There was no new constitutional order. Only the same old framework, now bent by the weight of democratic demand.

What sealed victory was unity and persistence. Wade had been contesting for years; when the moment was ripe, he and his allies seized it.

Lesson for Tanzania: Persistence matters. Unity matters more. Opposition leaders must learn to put egos aside and rally around a consensus candidate.

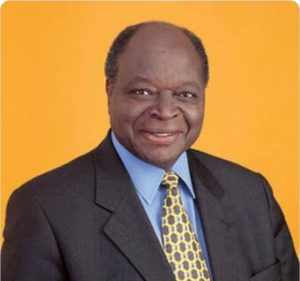

Kenya: The power of a grand coalition

Kenya’s story is particularly telling for Tanzania. In 1991, Section 2A of the constitution, which had cemented one-party rule, was repealed. Multiparty competition returned, but Daniel arap Moi’s KANU survived the first two elections (1992 and 1997) because the opposition was fragmented.

It was only in 2002, when the opposition finally united under the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), that KANU lost. Moi’s internal succession miscalculations and elite defections to the opposition sealed the party’s fate.

Lesson for Tanzania: Opposition fragmentation is the ruling party’s best insurance policy. Unity – and credible coalition management – is the opposition’s most powerful weapon.

Tanzania: To compete or not to compete?

This brings us back home. Tanzania’s opposition has been demanding constitutional reform for years. Our current framework centralises power in the presidency, undermines checks and balances, and leaves the opposition vulnerable.

In December 2024, Tanzania’s main opposition party, CHADEMA, launched the “No Reforms, No Election” campaign, immediately reacting to logistical injustices committed in the 2024 Local Government Elections.

Common understanding had it that the slogan meant a rallying cry for constitutional change and electoral justice. Within a month or so, the slogan carried a different, fundamentalist interpretation by the party’s own leadership – as a call to block the general election altogether.

The result of the unrealistic call eventually became a historic abstention from the 2025 general election, as reality unfolded that blocking the election was impractical. For the first time in the multiparty era, the main opposition party has boycotted a general election.

No ruling party in Africa has ever halted an election because the opposition demanded it. By stepping out of the race, CHADEMA ceded the field entirely to CCM, weakening its structures, eroding its grassroots visibility, and disappointing a score of citizens who expected a fight, however uneven.

A good number of its members defected to other parties seeking an opportunity to take part in the election, but the opposition movement was already weakened.

Tanzania’s opposition should have learnt a lesson from the experiences of Zambia, Malawi, Ghana, Senegal, and Kenya, where victories were possible under flawed constitutions.

So, should Tanzania’s opposition despair? Absolutely not. Should they abandon politics until a new constitution comes into effect? That would be political suicide.

What the opposition must do now. I have six suggestions:

Unite or perish. Kenya’s 1992 and 1997 elections prove that a divided opposition guarantees CCM victory. Unity is non-negotiable.

It’s a prerogative of the main opposition party to show leadership and influence in uniting all parties, failure to which guarantees the ruling party the same opportunity – influencing them in its favour.

Exploit CCM’s weaknesses. Economic mismanagement, corruption scandals, social injustices, and elite splits must be turned into political opportunities.

Offer a credible program. Zambians and Ghanaians voted for alternatives they believed could deliver. Tanzanians must be persuaded likewise.

Invest in grassroots mobilisation. Civic networks, youth movements, and digital platforms should be harnessed to reach every corner of the country.

Contest every seat. Boycotting elections or waiting for reforms cedes space to CCM and weakens opposition structures.

Prepare to govern. Post-victory disappointments in Zambia, Malawi, and Senegal show that removing an incumbent is only half the struggle. Institutional reform, anti-corruption safeguards, and service delivery must follow.

Politics does not wait

Tanzania deserves a new constitution, but waiting for one is not a proper strategy. The opposition’s duty is to compete, mobilise, and present Tanzanians with a credible alternative government, even under the current stringent rules.

The long game is to win power and then drive constitutional reform from a position of strength. Until then, unity, persistence, and credibility remain the surest tools for political change.

History has spoken. The question is whether Tanzania’s opposition is listening. And listening may not be enough. Acting precisely; and now.