WHEN President Samia Suluhu Hassan stood before a crowd of journalists at the Super Dome in Dar es Salaam on May 5, 2025, her message was loud and clear.

The president succinctly said Tanzanian journalists must be ethical, patriotic, and protective of the nation’s image.

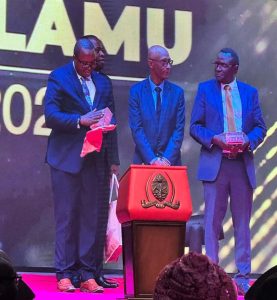

She was addressing journalists attending the Samia Kalamu Awards – a glamorous event celebrating excellence in journalism. It is an initiative to recognise and reward journalists for excellence in development journalism.

Organised collaboratively by the Tanzania Media Women’s Association (TAMWA) and the Tanzania Communications Regulatory Authority (TCRA), the awards aim to promote high-quality reporting on key national sectors such as health, energy, water, and governance.

President Samia stressed that media freedom is welcomed, but it must come with responsibility.

The underlying message, however, veered dangerously close to a familiar warning:

critique cautiously or risk being labelled unpatriotic.

This paradox sits at the heart of a growing tension between African regimes and their media ecosystems.

But it is reminiscent of her previous remark to journalists during celebrations of the World Press Freedom Day at Arusha in 2021, where she amphasised the need for “friendly journalism” with the government” by quoting an adage, “scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.”

Back then, this statement was widely interpreted as her attempt to establish a cooperative relationship with the media after years of repression under her predecessor, John Magufuli. However, critics and media freedom advocates raised concerns that such phrasing could imply conditional support and risk undermining journalistic independence.

The Samia Kalamu Awards, while a commendable initiative to uplift development journalism, raise difficult questions about the kind of journalism African leaders want and the kind that democracy truly needs.

The awards: Glory and gag in equal measure

Named after the sitting president herself, the awards are designed to reward Tanzanian journalists who engage in development-oriented storytelling.

Winners walked away with land plots, motorcycles, smartphones, and cash prizes up to TSh 10 million. Veteran journalists like Absalom Kibanda, Deodatus Balile, Mbaraka Islam, and Tido Mhando were among those honoured, especially for their roles in promoting national unity and political reporting.

While such recognition is important for morale in a struggling industry, the awards also set the tone for what kind of journalism is institutionally endorsed, meaning, narratives that align with state goals, that promote unity, and that steer clear of what the president termed “harmful” content.

But who defines what is harmful? And who ensures that the quest for patriotism does not morph into censorship?

Journalism in a time of repression

To understand the implications of President Samia’s call, one must examine Tanzania’s recent media history. Under President John Magufuli (2015–2021), Tanzania witnessed a sharp decline in media freedoms. Independent newspapers were suspended. Radio stations were shut down. Investigative journalists and bloggers were harassed, and draconian laws criminalised dissent. The chilling effect on free speech was palpable.

When Samia Suluhu Hassan took over in 2021, there was cautious optimism. She promised a new era of openness and dialogue.

Some banned newspapers were allowed back, and a few opposition figures returned from exile. But, the structural barriers to media freedom remained intact.

The same laws are still on the books. Journalists are still censoring themselves. Critical voices, especially online, are increasingly targeted under cybercrime laws.

This continuity has led some to argue that under Samia, the “death of journalism” has simply become more polished and more palatable, as repression is cleverly expressed in the language of reform.

The pitfalls of “patriotic journalism”

President Samia’s call for journalism that protects the nation’s image is not new in Africa. Leaders from Uganda to Rwanda, from Ethiopia to Egypt, have made similar appeals. The logic is simple: development requires unity; dissent breeds instability.

But this logic is flawed. Development without accountability leads to elite capture and widespread corruption.

In Tanzania, scandals like the Richmond energy contract, Tegeta Escrow, perennial corruption depicted in annual CAG reports, and questionable COVID-19 data reporting under Magufuli’s regime underscore the need for independent scrutiny.

By insisting on “patriotism,” leaders often blur the line between national interest and political self-preservation. In that situation, journalism becomes a mouthpiece, not a mirror.

What the president got right

To her credit, President Samia rightly highlighted the need for ethical journalism. In an era of fake news and digital misinformation, professionalism and factual integrity are more important than ever.

She also encouraged African journalists to tell their own stories rather than relying on Western media narratives, which often portray the continent in reductive or negative terms. This call for decolonising storytelling is both timely and valid.

What the president got wrong

But patriotism must not be conflated with compliance. True love for one’s country includes the courage to speak out against injustice.

Journalists who expose corruption, human rights abuses, or environmental degradation are not enemies of development. They are its vanguards.

A journalist investigating land grabbing in Rufiji or illegal logging in Katavi is doing more for Tanzania’s future than one who parrots state press releases. The same goes for those who cover police brutality, election irregularities, or gender-based violence. These are not anti-national stories. They are stories of the people.

The role of journalism in development

Development is not just about roads, bridges, and GDP. It is about freedom, dignity, and justice. Journalism plays a crucial role in all three. By informing citizens, exposing wrongs, and holding power to account, journalists create the conditions necessary for inclusive growth.

Tanzania needs journalism that investigates why girls drop out of school in rural Mbeya, why hospitals lack medicines in Kigoma, or why fishing communities in Mwanza are dying from pollution. It needs journalists who interrogate the role of foreign investors, the abuse of state apparatuses against politicians and critics, the influence of China, the misuse of public funds, and, in general, the shrinking civic space.

The way forward: A call to the media fraternity

The Samia Kalamu Awards should not become a velvet glove over an iron fist. The media fraternity in Tanzania and across Africa must embrace the awards with caution, recognizing their potential for both uplift and co-optation.

Adhering to their profession, journalists must:

– Insist on the repeal or reform of repressive laws. The Media Services Act, 2016, has many holes that need to be filled.

– Build coalitions to defend press freedom and protect each other from state harassment.

– Invest in investigative reporting and data journalism.

– Use new media to bypass censorship and reach wider audiences.

Media owners and editors must resist the temptation to curry favour with the state. Universities and journalism schools must nurture critical thinking, not conformity.

The international community must continue to support independent journalism, not just through funding but through political solidarity.

The mission of journalism must be reclaimed

The Samia Kalamu Awards have opened a national conversation about the role of journalism in Tanzania. That is a good thing. But if journalism is to reclaim its soul, it must go beyond praise and prizes. It must dare to ask hard questions, even of those who give the awards.

As Tanzanians prepare for the 2025 general elections, the media must decide whether to be cheerleaders or watchdogs. Because at the end of the day, a journalist’s true loyalty is not to the regime or even to the nation, but to the truth.

And the truth, as history shows, is the most patriotic story of all.